Abstract

The tree is a universal symbol found in the myths and sacred writings of all peoples. The psychologist Jung showed that the tree is part of the collective unconscious of all peoples, and frequently figures in dreams. The symbolic meanings of trees in dreams include growth, unfolding, shelter, nurture. In primal and shamanistic religions, the tree is regarded as the gatekeeper to the next world. Trees figure in all of the Dispensations of the Adamic cycle and in the Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, where they are used to explain many Bahá’í teachings. This paper surveys the symbolic use of trees in the world religions.

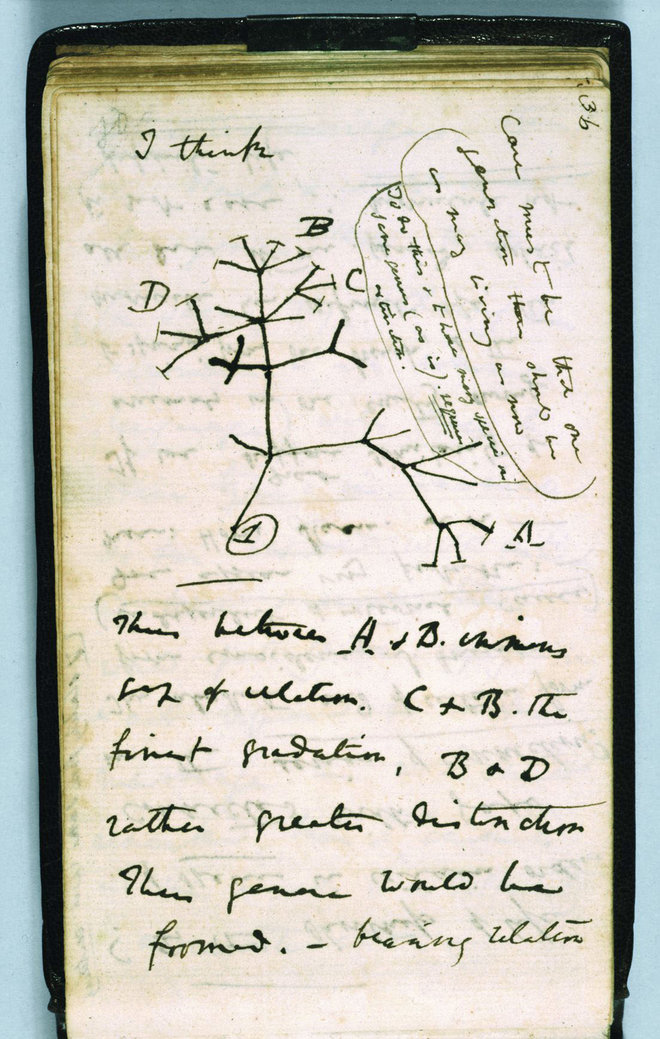

Darwin’s Tree of Life

Introduction

Trees are the largest and longest lived of all living things, and are used by humankind in numerous ways: shade, shelter and protection, for making fire, for fruit and nuts. Wine and mead are made from the sap; in deserts trees provide drinking water; medicine is made from leaves, stems and roots.

As a symbol, the tree is therefore rich in meanings. As well as their practical uses, trees also demonstrate the interconnectedness of leaves, stems and roots, the growth of a tall tree from a tiny seed and the amazing ability of trees to revive after winter or dry seasons. In some cultures, the tree represents the life of a human being – one is planted at the birth of each child and their fates are thought to be interlinked.

According to the Bahá’í Writings, spiritual truths can be learned from observing the physical universe. Bahá’u’lláh says that existence is a book,1 ‘revealing that which God has written therein.’2 Just as the Holy Writings have letters, words and verses, so also, according to ‘Abdu’l-Baha, ‘creation is in accord with the written word, and this is certain.’3 Bahá’u’lláh says that every created thing ‘is but a door leading into His (God’s) knowledge … a token of His power.’4 In other words, it is ‘a scroll that discloseth hidden secrets.’5

… the rays of the Sun of Truth are shed upon all things and shineth within them, and telling of the Daystar’s splendours,

Its mysteries, and the spreading of Its lights. Look thou upon the trees, upon the blossoms and fruits, even upon the stones. Here too wilt thou behold the Sun’s rays shed upon them, clearly visible within them and manifest by them.6

‘Abdu’l-Bahá furthermore states that one needs to understand the natural world in order to be able to understand the spiritual world: ‘Those who are uninformed of the world of reality and do not study created things, cannot investigate and discover hidden truths. They only have a superficial idea of things.’7

The tree and the collective unconscious

The psychologist Carl C. Jung, in many years of research, using drawings and dream analysis, explored the unconscious mind of people of different cultures. Fascinated by how often people dreamed of trees, he listed the various meanings of trees in dreams, drawings and fantasies. The commonest were growth, life, unfolding of form in a physical and spiritual sense, development, growth from below upwards and from above downwards, protection, shade, shelter, nourishing fruits, source of life, solidity, permanence, firm rootedness, being rooted to the spot, old age, personality, death and rebirth.8 He discovered that the images and meanings given to trees corresponded to the use of trees in ancient scripture, myth and poetry, of which the people had no prior knowledge. Jung concluded that the tree is an archetype: an element of the human collective unconscious – a symbol hard-wired into the brains of peoples of every culture.

The tree in primal and shamanistic religion

In ancient traditions all over the world, the tree is a symbol of life itself, representing the totality of a universe in which everything is imbued with spirit. This symbol is termed ‘the World Tree’:

Its trunk roots in the primeval depths and the mighty crown brings forth the multitude of creatures. In its seeds lie all species … the stars too were its fruits … the sap bestows all-knowledge and enlightenment … The far-branching World Tree is the invisible spiritual structure of the universe, the

material structure of which we perceive in spherical shapes and movements …

A mystical communion with (the World Tree) brings knowledge. This is why the Siberian shaman searches the World tree to climb it in order to reach the spirit world.9

The shaman believed that the Ruler of the World lives at the top of the World Tree. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá speaks of the World Tree as follows:

The Blessed Beauty … likened this world of being to a single tree, and all its people to the leaves thereof, and the blossoms and fruits. It is needful for the bough to blossom, and leaf and fruit to flourish, and upon the interconnection of all parts of the world-tree, dependeth the flourishing of leaf and blossom, and the sweetness of the fruit.10

Kar Morgenstern says:

Since time immemorial plants have played a key role in human spirituality. Their sublime beauty, entrancing scents … have suggested a connection with ‘the other world’, the non-material world of Gods and sprites, demons and devils. The spiritual world can be a terrifying place … traditionally the domain of the spiritual guides of a community, nowadays usually referred to as shamans … Shamans are usually chosen by an inner calling, they have no choice but to serve their community as ambassadors in the spiritual world.11

Trees represent the symbolic connection between the different levels of existence: the heavens above in its crown, the world of human affairs round its girth, and the underworld beneath its roots.12

Ancient Egyptian and Indian traditions noted that the tree crown resembled networks found in the geography of river deltas, the structure of the nervous system. Especially in the human brain, these networks resemble a tree crown, with the spinal chord being a ‘trunk.’

‘World Tree’, 2012. Land art installation by Hungarian artist Krisztián Balogh.

The tree and the Adamic cycle

The Bible begins and ends with the story of the Tree of Life. The Tree of Life was one of the two trees in the middle of the Garden of Eden. Adam and Eve ate, not of the Tree of Life, but of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.13 According to ancient Jewish tradition, these trees represented man. (The Tree of Knowledge is often assumed to be an apple tree, though this is an inference as neither the Tree nor its fruit is specifically named.) Because Adam ate of this tree, mankind was expelled from the Garden of Paradise and separated from the Tree of Life, lest he eat also of the Tree of Life and ‘live for ever.’14 The Qur’án’s version of the same story mentions a single tree, ‘the Tree of Eternity and the kingdom that faileth not.’15 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explains that sin is symbolised by the fruits of the tree of which Adam ate and which include ‘injustice, tyranny, hatred, hostility, strife which are the characteristics of the lower plane of nature.’16

However, the Bible predicts in Revelation that when Christ returns with the New Jerusalem, the Tree of Life will be growing there beside the water of life, ‘bearing twelve crops of fruit, yielding its fruit every month – and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations.’17 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá interprets this image thus: ‘The Tree of Life … is Bahá’u’lláh and the daughters of the kingdom are the leaves upon that blessed Tree.’18

Trees in Hinduism

In India, a tall, impressive fig tree (Ficus religiosa) – the banyan, asvattha, peepal or bo tree – is sacred. It is often worshipped as a daily morning ritual.19 In ancient times the wood was used to make fire by friction. Wild fig trees are also sacred all over Africa.20 In the Upanishads, the fruit of this tree is used as an example to explain the difference between the body and the soul: the body is like the fruit which, being outside, feels and enjoys sensory phenomena, while the soul is like the seed, which is inside and therefore witnesses these phenomena. The tree is sacred to the Hindu trinity of Vishnu, Shiva and Brahma. The roots are Brahma (the Creator), the trunk is Vishnu (energy) and the leaves are Shiva. The tree is closely related to Krishna, who is supposed to have died under it.21 This tree is mentioned twice in the Bhagavad

Gita: first, as one of the splendiferous manifestations of the Supreme Personality of the Godhead;22 secondly, in a teaching story. The reader is asked to imagine an upside-down banyan tree whose leaves are vedic hymns, the twigs the objects of the senses, the roots the achievements of human society. In this world, the real form of the tree cannot be perceived, but, according to the Gita, one must cut down this strongly rooted tree with the weapon of detachment in order to escape from entanglement with the material world and, having done so, surrender to the supreme God.23 Some Hindu scholars envisage the upside-down tree as a tree reflected in still water. This passage then refers to this world as an illusion, an image of the spiritual world which is the real world.24 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá confirms this idea: ‘the Kingdom is the real world, and this nether place is only a shadow … a shadow hath no life of its own, its existence is only a fantasy, and nothing more; it is but images reflected in water.’25

Trees in Judaism

God appeared to Moses in the Burning Bush, a burning thorn bush: ’ … God appeared to Him in flames of fire from within a bush. Moses saw that though the bush was on fire it did not burn up.’26 In the Qayyúmu’l-Asmá’ the Báb wrote: ‘I am the Flame of that supernal Light that glowed upon Sinai in the gladsome spot, and lay concealed in the midst of the Burning Bush.’27 Burning bush symbolism is used time and again in the Bahá’í writings, while tree of life symbolism is used in the Book of Proverbs:

‘(Wisdom) is a tree of life to those who embrace her’; ‘the fruit of the righteous is a tree of life’; ‘Hope deferred maketh the heart sick but a longing fulfilled is a tree of life’; ‘the tongue that brings healing is a tree of life, but a deceitful tongue crushes the spirit.’28

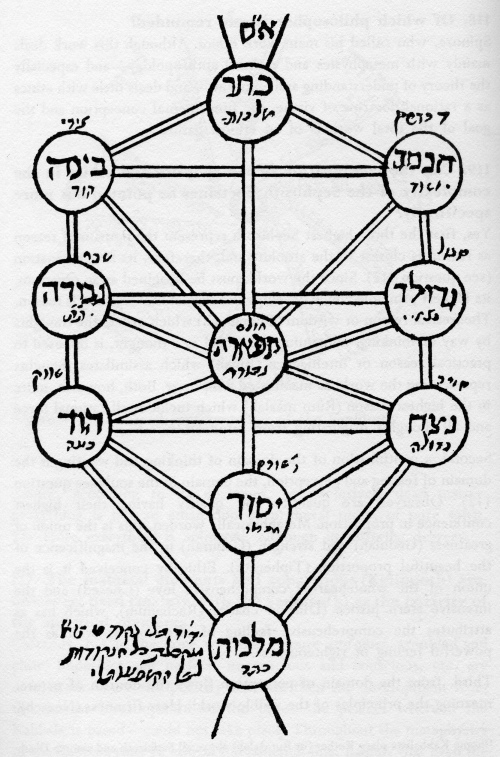

‘Tree of Life’ from a Zohar manuscript.

Trees in Zoroastrianism

The Tree of Life was considered by Zoroaster as the law itself and formed the centre of His philosophy and way of thinking. He said of the Tree of Life: ‘To the soul it is the way to heaven.’29 Trees are venerated by Zoroastrians: to destroy a tree is a sin.30

Trees in Buddhism

Gautama Buddha was seated beneath a tree, since then known as the Bodhi or Bo tree, ‘the tree of wisdom’ (Ficus religiosa), when He received enlightenment. To this day there are Bo trees in monasteries where Buddhists worship.31 He also used trees in His teaching, for example:

‘As a tree cut down sprouts again if its roots remain uninjured, even so, when the propensity to craving is not destroyed, this suffering arises again and again’; ‘It is well with the evil-doer until his evil (deed) bears fruit, then he sees its evil effects’; ‘it is ill perhaps, with the doer of good until his good deed ripens. But when it bears fruit, then he sees the happy results.’32

When in San Francisco ‘Abdu’l-Bahá told an Indian:

Man must irrigate the Blessed Tree which has eternal fruits and is the cause of life for all on earth. This goodly Tree, though hidden at first, will erelong envelop the whole world, and its leaves and branches will reach the heavens. It is like the Tree which Buddha planted: although at first it was a small sapling, it eventually enveloped the countries of Asia.33

Trees in Christianity

Jesus used the same tree and fruit metaphor used by Buddha to warn about false prophets:

By their fruit you will recognise them. Do people pick grapes from thornbushes, or figs from thistles? Likewise every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit. A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, and a bad tree cannot bear good fruit. Every tree that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire. Thus, by their fruit you will recognise them.34

In a profound passage, Jesus teaches the necessity of bearing fruit, while at the same time showing how the bearing of fruit entails suffering (such that suffering is equated with pruning). The passage also explains the nature of the covenant with the Manifestation:

I am the true vine, and my Father is the gardener. He cuts off every branch in me that bears no fruit, while every branch that does bear fruit he prunes so that it will be even more fruitful. You are already clean because of the word I have spoken to you. Remain in me, and I will remain in you. No branch can bear fruit by itself; it must remain on the vine. Neither can you bear fruit unless you remain in me.

I am the vine; you are the branches. If a man remains in me and I in him, he will bear much fruit; apart from me you can do nothing. If anyone does not remain in me, he is like a branch that is thrown away and withers; such branches are picked up, thrown into the fire and burned. If you remain in me and my words remain in you, ask whatever you wish, and it will be given you. This is my Father’s glory, that you bear much fruit, showing yourselves to be my disciples.35

The tree symbol comes into the prophecy of the two witnesses in the Book of Revelation, who ‘will prophesy for 1,260 days’: these are the two olive trees and the two lampstands that stand before the Lord of the earth.36 In Some Answered Questions, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá explains that these two trees symbolise Muhammad, the Messenger of God, and the Imám Alí.37

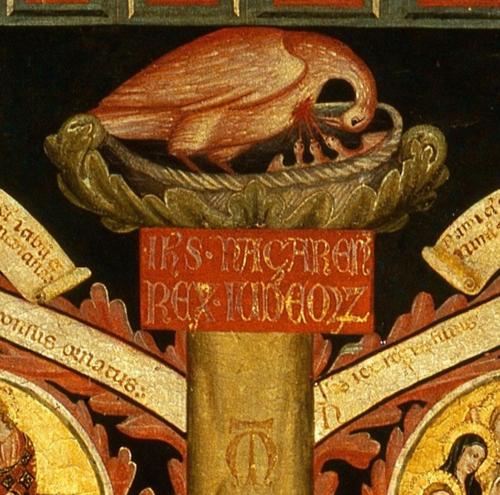

‘The Tree of Life’ (detail), Pacino di Bonaguida, 1303-1339.

Trees in Islam

In Islam the Sadratu’l-Muntahá, literally ‘the crown of the jujube tree’, is variously translated as Lote Tree of the Extreme Limit, the Sidrah tree which marks the boundary or ‘the furthermost Lote-Tree’.38 (The term was translated by Shoghi Effendi as ‘the Tree beyond which there is no passing.’)39 The tree is Ziziphus jujuba, a leguminous, prickly plum tree used for hedges. In India, a decoction of its leaves is used to wash the dead on account of the sacredness of the tree.40 The Sadratu’l-Muntahá is used to describe the spiritual experiences of Muhammad in His encounter with God during the Revelation of the Qur’án:

The Koran is no other than a revelation revealed to Him. One terrible in Power taught it Him, endued with wisdom. With even balance stood He in the highest part of the horizon: then came He nearer and approached, and was at the distance of two bows, or even closer, and He revealed to His Servant what He revealed … He had seen Him also another time, near the Sidrah-tree, which marks the boundary, near where is the garden of repose. When the Sidrah tree was covered with what covered it, His eye turned not aside, nor did it wander: for he saw the greatest of the signs of His Lord.41

The two bows are understood as the two arcs of a circle caused by the descent of God and the ascent of His servant to meet Him.42 According to Rodwell’s notes, the Sidrah tree ‘covered with what it covered it’ means hosts of adoring angels, by which the tree was masked.

This symbol is also used in the accounts of Muhammad’s Night Journey to mark the point in the heavens beyond which neither men nor angels can pass in their approach to God and thus to delimit the bounds of divine knowledge that can be revealed to mankind (see note 42).

To Muslims, the Sadratu’l-Muntahá symbolises a station of spirituality, the extreme limit of human development. It is the moment when a person finds himself between the Hands of God. Muslims consider this Lote Tree of the Extreme Limit to be the very inner content of Ritual Prayer.

In another significant passage in the Qur’án we find the significant use of a symbolic olive tree:

God is the light of the Heavens and the Earth. His Light is like a niche in which is a lamp – the lamp encased in glass – the glass, as it were, a glistening star. From the blessed tree it is lighted, the olive neither of the East nor of the West, whose oil would well nigh shine out, even though fire touched it not! He is light upon light. God guideth whom He will to His light, and God setteth forth parables to men, for God knoweth all things.43

Shoghi Effendi clarified that this Olive Tree is the Báb, and the release of the oil is a symbol of His martyrdom, which shed light on all humankind. In the Qayy’úmu’l-Asmá’, the Báb wrote: ‘I am the Lamp which the Finger of God hath lit within its niche and caused to shine with deathless splendour’ (see note 27).

Trees in the Bahá’í Faith

Bahá’u’lláh described Himself as a tree. In Hidden Words we find the Tree of Life, the Tree of Wealth, the Tree of Love. Moreover, He referred to all female believers as leaves of this tree, and to all males as branches. In important passages, when referring to Himself as a Manifestation of God, Bahá’u’lláh uses the term Sadratu’l-Muntahá or Divine Lote Tree, i.e. ‘the tree beyond which there is no passing.’44 For instance, in the Kitáb-i-Aqdas He counsels: ‘Advance, O people, unto the blest and crimson spot, wherein the Sadratu’l-Muntahá is calling “Verily, there is none other God beside me, the Omnipotent Protector, the Self-Subsisting”’45 and ‘Give ear unto the verses of God which He who is the Sacred Lote-Tree reciteth unto you.’46 And in the Medium Obligatory Prayer: ‘He in truth, hath manifested Him Who is the Dayspring of Revelation, Who conversed in Sinai, through whom the Supreme Horizon hath been made to shine, and the Lote Tree, beyond which there is no passing, hath spoken.’

Furthermore, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá is the Greatest Branch of the Divine Lote Tree, as powerfully described by Bahá’u’lláh in the Tablet of the Branch.47 In the Ridván Tablet, the imagery of tree foliage is used very vividly:

This is the Paradise on whose foliage the wine of utterance hath imprinted the testimony … the rustling of whose leaves proclaims: ‘He who, from everlasting, had concealed His Face from the sight of creation is now come.’

The tree symbol was also used by the Báb, Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to explain many of their teachings. The oneness of God can be likened to a tree. The Báb wrote: ‘O Lord! Provide for the speedy growth of the Tree of Thy divine Unity.’48 The renewal of religion or progressive revelation can be likened to the cycle of a fruit tree growing old and bearing no fruit: ‘Then doth the Husbandman of Truth take up the seed from the same tree, and plant it in a pure soil; and there standeth the first tree, even as it was before.’49 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá used this analogy on other occasions.

The renewal of religion is like the response of trees to the cycle of the seasons:

From the seed of reality religion has grown into a tree which has put forth leaves and branches, blossoms and fruit. After a time this tree has fallen into a condition of decay. The leaves and blossoms have withered and perished; the tree has become stricken and fruitless. It is not reasonable that man should hold to the old tree, claiming that its life-forces are undiminished, its fruit unequalled, its existence eternal. The seed of reality must be sown again in human hearts in order that a new tree may grow therefrom and new divine fruits refresh the world. By this means the nations and peoples now divergent in religion will be brought into unity, imitations will be forsaken, and a universal brotherhood in reality itself will be established, warfare and strife will cease among mankind; all will be reconciled as servants of God. For all are sheltered beneath the tree of His providence and mercy … 50

With regard to the oneness of humankind, Bahá’u’lláh’s pivotal teaching, several tree images are used. One is the image of all the people of the world being ‘beneath the shadow of the Tree of His care and loving-kindness.’51 A second image is the following metaphor: ‘Ye are the fruits of one tree, and the leaves of one branch. Deal ye one with another with the utmost love and harmony, with friendliness and fellowship.’52 A third image is that of different peoples resembling the different organs, branches, leaves, buds and fruit of one tree: ‘Think of all men as being flowers, leaves or buds of this tree, and try to help each and all to realise and enjoy God’s blessings. God neglects none: He loves all.’53 A fourth image uses the tree which flourishes only when the organs function in co-operation in order to emphasise the need for interconnectedness among the members of humanity: ‘For this reason must all human beings powerfully sustain one another …

Let them … behold all humanity as leaves and blossoms and fruits of the tree of being. Let them at all times concern themselves with doing a kindly thing for one of their fellows, offering to someone love, consideration, thoughtful help.’54 A fifth image emphasises the beauty of diversity:

Behold a beautiful garden full of flowers, shrubs and trees … The trees too, how varied are they in size, in growth, in foliage – and what different fruits they bear! Yet all these flowers, shrubs and trees spring from the self-same earth, the same sun shines upon them and the same clouds give them rain … 55

In relation to the purpose of our lives, Christ emphasised the importance of leading a fruitful life. Bahá’u’lláh explains what the appropriate fruits might be:

each tree yieldeth a certain fruit, and a barren tree is but fit for the fire … The fruits that best befit the tree of human life are trustworthiness and godliness, truthfulness and sincerity; but greater than all, after recognition of the unity of God, praised and glorified be He, is regard for the rights that are due to one’s parents … 56

This analogy is further elucidated by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá to explain the relationship between prosperity and virtue:

material comforts are only a branch, but the root of the exaltation of man is the good attributes and virtues which are the adornments of his reality. These are the divine appearances, the heavenly bounties, the sublime emotions, the love and knowledge of God; universal wisdom, intellectual perception; scientific discoveries, justice, equity, truthfulness, benevolence, natural courage and innate fortitude; the respect for rights and the keeping of agreements and covenants; rectitude in all circumstances; serving the truth under all conditions; the sacrifice of one’s life for the good of all people; kindness and esteem for all nations; obedience to the teachings of God; service to the

Divine Kingdom; the guidance of the people, and the education of the peoples and races.57

Bahá’u’lláh uses a vivid metaphor to solve the knotty theological problem about whether an individual is saved by faith or saved by deeds – the two are inseparable: ‘Regard thou faith as a tree. Its fruits, leaves, boughs and branches are, and have ever been, trustworthiness, truthfulness, uprightness and forbearance.’58

Another metaphor for faith is the seed, which will grow into a tree:

Lift up your hearts above the present and look with eyes of faith into the future! Today the seed is sown … but behold the day will come when it shall rise a glorious tree and the branches thereof shall be laden with fruit.59

Bahá’u’lláh uses a tree simile to explain how the soul is invisible, even though its development is so important:

… the fruit, ere it is formed, lieth potentially within the tree. Were the tree to be cut into pieces, no sign nor any part of the fruit, however small, could be detected … Certain fruits, indeed attain their fullest development only after being severed from the tree.60

‘Abdu’l-Bahá also uses the tree describe the connection between soul and spirit:

the soul is the intermediary between the body and the spirit. In like manner is this tree [a small orange-tree on the nearby table] the intermediary between the seed and the fruit. When the fruit of the tree appears and becomes ripe, then we know that the tree is perfect; if the tree bore no fruit it would be merely a useless growth serving no purpose!

When a soul has in it the life of the spirit, then does it bring forth good fruit and become a Divine Tree.61

He used the tree symbol to comfort a bereaved mother:

… the Merciful Gardener, if He loves a young tree, takes it out from among the others and carries it from the restrictions of narrowness to a large farm and a beautiful flourishing garden, in order that the young tree may develop, its branches grow high, its flowers open, its fruits appear and its shadow expand. But the rest of the trees do not know this, because this is a hidden mystery which becomes unfolded to us in the eternal kingdom.

A similarly gorgeous metaphor was used in a letter to a wife, recently widowed: ‘Grieve not therefore and be not despondent … strive that the orchard of his highest wish may abound with fruitful trees.’

‘Abdu’l-Bahá uses the symbol of the seed becoming a tree to illustrate spirituality and the consequences of sacrifice:

If you plant a seed in the ground, a tree will become manifest from that seed. The seed sacrifices itself to the tree that will come from it. The seed is outwardly lost, destroyed; but the same seed which is sacrificed will be absorbed and embodied in the tree, its blossoms, fruit and branches. If the identity of that seed had not been sacrificed to the tree which became manifest from it, no branches, blossoms or fruits would have been forthcoming. Christ outwardly disappeared. His personal identity became hidden from the eyes, even as the identity of the seed disappeared; but the bounties, divine qualities and perfections of Christ became manifest in the Christian community which Christ founded through sacrificing Himself. When you look at the tree, you will realize that the perfections, blessings, properties and beauty of the seed have become manifest in the branches, twigs, blossoms and fruit; consequently, the seed has sacrificed itself to the tree. Had it not done so, the tree would not have come into existence. Christ, like unto the seed, sacrificed Himself for the tree of Christianity. Therefore, His perfections, bounties, favors, lights and graces became manifest in the Christian community, for the coming of which He sacrificed Himself.62

Of the Word of God, Bahá’u’lláh writes:

The word of God may be likened to a sapling, whose roots have been implanted in the hearts of men. It is incumbent upon you to foster its growth through the living waters of wisdom, of sanctified and holy words, so that its root may become firmly fixed and its branches may spread out as high as the heavens and beyond.63

‘Abdu’l-Bahá in turn uses the example of exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between plants and animals as a metaphor for co-operation, which is ‘One of the greatest foundations of the religion of God.’ He continues:

For the world of humanity, nay rather all the infinite beings exist by this law of mutual action and helpfulness …

When one considers the living things and the growing plants, he realised that the animals and man sustain life by having the emanations of the vegetable world, and this fiery element is called oxygen. The vegetable kingdom also draws life from the living creatures in the substance called carbon.

In brief, the beings of sensation acquire life from the growing beings and, in turn, the growing things receive life from the sensitive creature. Therefore this interchange of forces and inter-connectedness is continual and uninterrupted.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá used trees to illustrate the equal rights of men and women:

God has created all creatures in couples … and there is absolute equality between them.

In the vegetable world there are male plants and female plants, they have equal rights, and possess an equal share of the beauty of their species; though indeed the tree that bears fruit might be said to be superior to that which is unfruitful.64

Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá also use trees to illustrate the difference in functions of men and women: ‘The Tree of Life, of which mention is made in the Bible, is Bahá’u’lláh, and the daughters of the Kingdom are the leaves upon that blessed Tree’ (see note 18). Women are generally called leaves and men branches in the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh. This paints a picture of the strong branches holding the leaves up to the sunlight where they can photosynthesise and produce nourishment for the tree, neither being able to function fully without the other.

Teaching the faith is like watering parched souls: ‘even as the clouds of heaven, shed ye life upon field and hill, and like unto April winds, blow freshness through these human trees, and bring them to their blossoming.’65

‘Abdu’l-Bahá repeats the tree metaphor used by Christ to explain how the individual must be part of a religion in order to be fruitful, just as branches cut off from the root bear no fruit.66 At another time He described this faithfulness to the Covenant as resembling the maintaining of the tree’s root. Independent action, like an uprooted plant, will not survive:

… all the forces of the universe, in the last analysis serve the Covenant … what can these weak and feeble souls achieve? Hardy plants that are destitute of roots and are deprived of the outpourings of the cloud of mercy will not last.67

‘Abdu’l-Bahá uses trees to explain the relative importance of both nature and nurture in education. One cannot change a seed from one species of tree into another even as

education cannot alter the inner essence of a man, but it doth exert tremendous influence, and from this power it can bring forth from the individual whatever perfections and capacities are deposited within him. A grain of wheat, when cultivated by the farmer, will yield a whole harvest, and a seed, through the gardener’s care, will grow into a great tree. Thanks to a teacher’s loving efforts, the children of the primary school may reach the highest levels of achievement; indeed, his benefactions may lift some child of small account to an exalted throne … 68

Conclusion

Given the richness of symbolic meanings of trees and the spiritual and social truths which they help us understand, it is not surprising to find that Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá experienced great joy in being near trees, and wanted the same for all people. In 1912, when in Dublin in the United States, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá said:

How calm it is. No disturbing sound is heard. When a man observes the wafting of the breeze among these trees, he hears the rustling of the leaves and sees the swaying of the trees; it is as though all are praising and acknowledging the One True God.69

Later the same year while in New York City, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá walked to Broadway and Central Park. He was not pleased with the dense population and the height of the buildings, saying: ‘These are injurious to the public health. This population should be in two cities, the buildings should be lower and the streets should be tree-lined as they are in Washington.’70

(‘The Use of Trees as Symbols in the World Religions’, by Sally Liya. Published in Solas, 4, pages 41-58. Donegal, Ireland: Association for Baha’i Studies English-Speaking Europe, 2004)

References

1. Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 60.

2. Ibid. p. 141.

3. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Makatib Vol. 1.

4. Bahá’u’lláh quoted in Crown of Beauty p. 67.

5. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá p. 41.

6. Ibid. pp. 41-2.

7. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá quoted in Mahmoud’s Diary p. 423.

8. Jung, C. J. ‘On the history and interpretation of the tree symbol,’ pp. 272-349 in Alchemical Studies (trans. RFC Hull, 1967).

9. Hageneder, F. 2001 Die Andere Realität (Munich, 2001) http:spirit-of-trees.net/tree_of_life_e.html.

10. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá p. 1.

11. Morgenstern, Kar Plants as Gateways to the Sacred (Sacred Earth, 2003); http://www.sacred.earth.com/Sacred.htm

12. Hageneder, F. Die Andere, Realität (Munich, 2001) http//spirit-of-trees.net/tree_of_life_e.html.

13. Genesis 2:9.

14. Ibid. 3:23-25.

15. Qur’án 20:118.

16. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Paris Talks p. 177.

17. Revelations 22:2.

18. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá p. 57.

19. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, A. C. The Bhagavad Gita as it is (The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1983).

20. Mbiti, J. S. African Religions and Philosophy (second edition, Heinemann, 1989) p. 51.

21. http://www.gujari.net/ico/Mystica/html/peepal_tree.htm.

22. Bhagavad Gita, 10:28.

23. Ibid., 15:1-4.

24. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, A. C. The Bhagavad Gita as it is (The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust, 1983).

25. Selections of the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá p. 178.

26. Exodus 3:6.

27. Quoted by Shoghi Effendi in The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh: Selected Letters p. 126.

28. Proverbs 3:18, 13:12, 11:30, 15:4.

29. (http://spirit of trees.net/tree_of_life_e.html)

30. (UNESCO assisted Parsi Zoroastrian project

http://www.unescoparzor.com/project/religion.htm

31. Rahula, W. What the Buddha taught (Gordon Fraser, Bedford, 2nd Edition, 1967) p. 81.

32. Dhammapada, 338, 119, 120.

33. Mahmoud’s diary, San Francisco, 11 October 1912.

34. Matthew 7:16-20.

35. John 15:1-5.

36. Revelation 11:3-4.

37. ‘Abdul-Baha Some Answered Questions pp. 49-50.

38. Rodwell, J.M., The Qur’án (Notes) p. 487.

39. Baha’u’llah The Kitáb-i-Aqdas p. 220.

40. Theobald, Erwann Les energies Benefiques des Arbres (Editions trajectoire, 1985) p. 111.

41. Qur’án 53:4-18.

42. Zuhri, Muhammad The Lote Tree of the Extreme Limit (1999)

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/5739/sidratul-muntaha-e.htm

43. Qur’án 24:35.

44. Bahá’u’lláh The Kitáb-i-Aqdas p. 220. 58

45. Ibid. para., 100.

46. Ibid. para. 148.

47. Bahá’u’lláh Tablet of the Branch quoted in Shoghi Effendi The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh: Selected Letters pp. 134-5.

48. A Compilation of Passages from the Writings of the Báb p. 44.

49. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá p. 52.

50. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá The Promulgation of Universal Peace pp. 141-2.

51. Gleanings p. 6.

52. Ibid. p. 287.

53. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Paris Talks p. 170.

54. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá p. 1.

55. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Paris Talks 28 October p. 51.

56. Kitáb-i-Aqdas p. 139.

57. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Some Answered Questions pp. 79-80.

58. Bahá’u’lláh quoted in Trustworthiness, compiled by the Universal House of Justice.

59. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Paris Talks p. 68.

60. Bahá’u’lláh Gleanings p. 155.

61. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Paris Talks p. 98.

62. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá The Promulgation of Universal Peace p. 151.

63. Bahá’u’lláh Gleanings p. 97.

64. ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Paris Talks p. 161.

65. Selections from the Writings of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá p. 246.

66. Ibid. pp. 234-38.

67. Ibid. p. 228.

68. Ibid. p. 132.

69. Ibid. Mahmoud’s Diary p. 192.

70. Ibid. p. 403.